Where There's a Will...

|

| Sister Susan with James Hays's Will |

In

a card catalog drawer in the Bellefonte Historical Museum, I found a

card with my third great-grandfather's name on it: James Hays. My

sister Susan and I had traveled to Pennsylvania in search of

information about any Hays ancestor, and here was a card

promising information regarding our Revolutionary War ancestor who

settled here in Centre County. James had lived, raised his family,

and died in the small town of Beech Creek near Bellefonte. The card

indicated there was a will to be had.

I

took the card over to the librarian, expecting her to tell me that to

see the will I would need to go over to the county courthouse. I was

not looking forward to walking uphill in the heat to get to the

courthouse, so I was relieved to learn that the will resided right

there in the building we were in. Down in the basement. She said

she'd go downstairs to retrieve it. That is, if she could get

to it. They were doing some remodeling down there, so the box with my

will just might be in an inaccessible part of the basement. As she

made her descent, my sister Susan, a former historical society

archivist herself, made some dire comments on the unsuitability of

basements as storage spaces. I waited apprehensively, fearing that

the librarian would return empty-handed or bearing a disintegrating,

moldy, unreadable will. But when she came back upstairs she presented

us with a lily-white packet, measuring about 4x7 inches, bound by a

white ribbon tied in a bow.

Susan

and I began to unpack the envelope which contained not just a will,

but every document that had anything to do with the administration of

the will: an inventory of all of my ancestor's possessions, a

document naming the executor and witnesses of the will, and many tiny

scraps of paper that I believed to be receipts signed by the various

beneficiaries, stating what had been distributed to them.

I

loved the inventory—One Heifer...One Stear...Two Horses with their

Geers...Small Speckled D° (I have no idea!)...Harrow pins, etc. Also

listed was income from the sale of land in nearby Lycoming County.

All told, eleven farm items, nine household items, and two bonds were

listed. Total value? $2190.16.

|

| First page of inventory |

The

next thing I loved about the will was that a witness and executor of

it was another third great-grandfather of mine! Gideon Smith

and James Hays were each father-in-law to the other's child. Gideon's

daughter Susannah Sally married James's son Samuel. Although James

was a good twelve years older than Gideon, they were good friends. In

designating Gideon an executor of his will, James refers to him as a

Trusty friend.

|

| Signature of Gideon Smith |

When it came to the unfolding of the tiny scrap receipts, I began to get nervous that we'd never get them refolded and back in the right order. It did occur to me that maybe I didn't need to worry. Was there anyone else in the world who would ever care, who would be wanting to look at this will packet again? (Come to think of it, was there ever anyone before me who had opened this envelope? Or was the first time since my ancestor's death that his will and all its accompanying documents had ever seen the light of day?) I decided that, in order to cause the least disruption possible, I would take a photo of one receipt--with Susan holding down the corners to keep it flat--just to have as an example. The one I photographed was a receipt signed by one of Gideon's sons!

|

Finally

I came to the will itself. I checked the exact date and learned that

James had made out his will a few weeks before his death. The

language took me back to the world of 1817: Knowing that it is

apointed for all Men once to die I so make and publish this my Last

will and Testament.

The

first beneficiary, of course, was his wife Sarah Brown Hays, my third

great-grandmother. The provisions he made for his helpmeet of

fifty-eight years I found quite touching.To

Sarah, James bequeathed the following: two bonds of fifty pounds

each, one bed and beding, one cow (her choice of the flock,) six

sheep, a set of drawers, one-third of the kitchen furniture,

one-fourth of the chairs, and the fire irons. (Evidently all of

the fire irons as no others were designated for other heirs.) Sarah

was also guaranteed the use of the room where I now ly. I

pictured the scribe sitting next to the bed of the dying James Hays,

writing down all his wishes. Was it an attorney? Would it have to

have been an attorney or could anybody have recorded what James

dictated as long as Gideon and the neighbor, William Feron, were

there to witness it? (There's so much I don't know about wills!)

James

further orders that their son, my second great-grandfather Samuel,

find her a horse to ride when she chuses. Later on in the will

he specifies that she and their one unmarried daughter will stay in

the house as long as it suits them and that Samuel, again, will see

that they live in as comfortable acomodations as they have

heretofore had.

Poor

Samuel, the youngest of the family, in charge of everything. Only

twenty-five years old at the time of his father's death, he is

suddenly responsible for sorting out everything—the running of the

farm and seeing that the needs of his mother and his maiden sister

are met. Why doesn't his brother John have to do any of the heavy

lifting? After all, he is the older son and doesn't live that far

away. But maybe Samuel is the responsible one, the one who had stayed

on the scene to farm alongside his father, the one who knows what's

what. I'm sure James had his reasons.

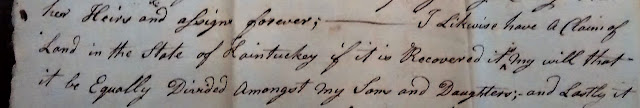

One

final gem I found in the will was the following: I likewise have a Claim of Land in the State of Kaintuckey if it is Recovered it is my will that it be Equally Divided amongst my Sons and Daughters

I had read in other sources that Lieutenant James Hays had received three tracts of land as payment for his military service in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. One was the Beech Creek property, the second was also in Pennsylvania. But I had never been able to determine the location of the third claim and had always been curious about why he had never followed up on it. Now I'm wondering if, in that packet in the Bellefonte basement, there might be an overlooked scrap of paper holding that information. Perhaps the executors of James's will had attempted to track down the Kaintuckey claim and had reported their success or failure in finding it. (As I say, I know very little about how these things work. Maybe a Wills 101 course should be next in my genealogy self-education.)

James Hays died on February 14, his wife's birthday, in 1817. He was seventy-six years old.