The Old Homestead

Are You My Great Grandmother?

The adventures and misadventures of a family history researcher

Sunday, April 1, 2018

Tuesday, March 20, 2018

52 Ancestors Week 10 prompt: Strong Woman

A Strong Woman

Barbro Helgesdatter Aasli Gaarder must have been a strong woman. At least I hope she was. But when I see the haunted look on her face in the only photo I have of her, I have to wonder.

I can only guess at how she might have responded to the difficult events in her life. There are no letters between Barbro and friends or family members, no diary. All I have to go on are the antiseptic census records, dates of births and deaths, accounts of her husband's achievements, and her obituary.

Barbro was a month shy of seventeen years when she gave birth to her first child, and she continued to bear another child about every other year until she had produced thirteen. That alone should qualify her as a strong woman.

And then consider that in 1849 she and her husband Syver Guttormsen Gaarder left their farm and all that made up their life in the Valdres valley of Norway to make a new home in Wisconsin. In the port of Drammen, they boarded the sailing ship Benedicte with their brood, which at the time numbered ten. The youngest was four months old when they sailed. They spent the next ten weeks at sea. When they arrived in the New York harbor they still had to make their way to the Erie Canal, to Milwaukee, and from there to the parsonage in Rock County where they were expected. The pastor there offered temporary shelter for immigrating Norwegians until they could find land on which to settle.

Barbro's husband left her at the parsonage with the ten children in order to scout out land in nearby Green County. Granted, her oldest children were in their twenties, and she had a twenty-three-year-old daughter-in-law, so presumably she had help—but still!

Syver did indeed find land in Green County and bought 160 acres in the township of Albany. There was already a log house in place and that is where, with an addition built onto it, the family of thirteen lived. When a few more Norwegian families came along to settle in Albany, the Gaarder's log home also became the meeting place for church and school. I picture Barbro managing not just a household, but a community center! To have no privacy, to be responsible for accommodating the whole community! To me that sounds like quite a bit of responsibility. But of course I have no way of knowing how Barbro felt about all of this. Perhaps, rather than being burdened, she enjoyed the company of all those people. Perhaps they provided a lot of support.

Once settled in Albany, Barbro continued to have babies. But just weeks after baby Ellef came along in February of 1851, her daughter Live died at the age of eighteen. How did Barbro bear it? Another baby, Sever, arrived in 1853. Things were quiet until 1855 when Guttorm, her first-born, fell from the top of a haystack, landed on the prongs of a pitchfork piercing his intestines. He died within a couple of days. About ten months later, on her own birthday, Barbro gave birth to her final child, Julia Gunhild.

Barbro was forty-six, had given birth to thirteen children, had seen two die, and still had another forty years or so to live. To the best of my knowledge, her next big loss was the death of her husband in 1881. Syver was about ten years her senior and died when Barbro was seventy-one. She had sixteen more years to live. Hopefully she was able to enjoy her prodigious family for a good long time before she had the stroke that immobilized her for the last three years of her life. To quote from her obituary,

I can only guess at how she might have responded to the difficult events in her life. There are no letters between Barbro and friends or family members, no diary. All I have to go on are the antiseptic census records, dates of births and deaths, accounts of her husband's achievements, and her obituary.

Barbro was a month shy of seventeen years when she gave birth to her first child, and she continued to bear another child about every other year until she had produced thirteen. That alone should qualify her as a strong woman.

And then consider that in 1849 she and her husband Syver Guttormsen Gaarder left their farm and all that made up their life in the Valdres valley of Norway to make a new home in Wisconsin. In the port of Drammen, they boarded the sailing ship Benedicte with their brood, which at the time numbered ten. The youngest was four months old when they sailed. They spent the next ten weeks at sea. When they arrived in the New York harbor they still had to make their way to the Erie Canal, to Milwaukee, and from there to the parsonage in Rock County where they were expected. The pastor there offered temporary shelter for immigrating Norwegians until they could find land on which to settle.

Barbro's husband left her at the parsonage with the ten children in order to scout out land in nearby Green County. Granted, her oldest children were in their twenties, and she had a twenty-three-year-old daughter-in-law, so presumably she had help—but still!

Syver did indeed find land in Green County and bought 160 acres in the township of Albany. There was already a log house in place and that is where, with an addition built onto it, the family of thirteen lived. When a few more Norwegian families came along to settle in Albany, the Gaarder's log home also became the meeting place for church and school. I picture Barbro managing not just a household, but a community center! To have no privacy, to be responsible for accommodating the whole community! To me that sounds like quite a bit of responsibility. But of course I have no way of knowing how Barbro felt about all of this. Perhaps, rather than being burdened, she enjoyed the company of all those people. Perhaps they provided a lot of support.

Once settled in Albany, Barbro continued to have babies. But just weeks after baby Ellef came along in February of 1851, her daughter Live died at the age of eighteen. How did Barbro bear it? Another baby, Sever, arrived in 1853. Things were quiet until 1855 when Guttorm, her first-born, fell from the top of a haystack, landed on the prongs of a pitchfork piercing his intestines. He died within a couple of days. About ten months later, on her own birthday, Barbro gave birth to her final child, Julia Gunhild.

Barbro was forty-six, had given birth to thirteen children, had seen two die, and still had another forty years or so to live. To the best of my knowledge, her next big loss was the death of her husband in 1881. Syver was about ten years her senior and died when Barbro was seventy-one. She had sixteen more years to live. Hopefully she was able to enjoy her prodigious family for a good long time before she had the stroke that immobilized her for the last three years of her life. To quote from her obituary,

- Through her whole life, she was a faithful and devoted member of her church, and until sickness deprived her of her power of speech, she frankly confessed her faith in the atoning sacrifice of her Savior.

- But then, you know how obituaries are: the subjects always face life bravely, never lose their faith, always die with equanimity. How much can one believe in a characterization in an obituary?

- As I say, I can only hope that my great-great-grandmother Barbro was strong.

- Melissa Hays →Thad Hays →Hannah Gaarder →Helge Gaarder →Barbro Helgesdatter Gaarder

Sunday, March 11, 2018

52 Ancestors Week 9: Where There's a Will

Where There's a Will...

|

| Sister Susan with James Hays's Will |

In

a card catalog drawer in the Bellefonte Historical Museum, I found a

card with my third great-grandfather's name on it: James Hays. My

sister Susan and I had traveled to Pennsylvania in search of

information about any Hays ancestor, and here was a card

promising information regarding our Revolutionary War ancestor who

settled here in Centre County. James had lived, raised his family,

and died in the small town of Beech Creek near Bellefonte. The card

indicated there was a will to be had.

I

took the card over to the librarian, expecting her to tell me that to

see the will I would need to go over to the county courthouse. I was

not looking forward to walking uphill in the heat to get to the

courthouse, so I was relieved to learn that the will resided right

there in the building we were in. Down in the basement. She said

she'd go downstairs to retrieve it. That is, if she could get

to it. They were doing some remodeling down there, so the box with my

will just might be in an inaccessible part of the basement. As she

made her descent, my sister Susan, a former historical society

archivist herself, made some dire comments on the unsuitability of

basements as storage spaces. I waited apprehensively, fearing that

the librarian would return empty-handed or bearing a disintegrating,

moldy, unreadable will. But when she came back upstairs she presented

us with a lily-white packet, measuring about 4x7 inches, bound by a

white ribbon tied in a bow.

Susan

and I began to unpack the envelope which contained not just a will,

but every document that had anything to do with the administration of

the will: an inventory of all of my ancestor's possessions, a

document naming the executor and witnesses of the will, and many tiny

scraps of paper that I believed to be receipts signed by the various

beneficiaries, stating what had been distributed to them.

I

loved the inventory—One Heifer...One Stear...Two Horses with their

Geers...Small Speckled D° (I have no idea!)...Harrow pins, etc. Also

listed was income from the sale of land in nearby Lycoming County.

All told, eleven farm items, nine household items, and two bonds were

listed. Total value? $2190.16.

|

| First page of inventory |

The

next thing I loved about the will was that a witness and executor of

it was another third great-grandfather of mine! Gideon Smith

and James Hays were each father-in-law to the other's child. Gideon's

daughter Susannah Sally married James's son Samuel. Although James

was a good twelve years older than Gideon, they were good friends. In

designating Gideon an executor of his will, James refers to him as a

Trusty friend.

|

| Signature of Gideon Smith |

When it came to the unfolding of the tiny scrap receipts, I began to get nervous that we'd never get them refolded and back in the right order. It did occur to me that maybe I didn't need to worry. Was there anyone else in the world who would ever care, who would be wanting to look at this will packet again? (Come to think of it, was there ever anyone before me who had opened this envelope? Or was the first time since my ancestor's death that his will and all its accompanying documents had ever seen the light of day?) I decided that, in order to cause the least disruption possible, I would take a photo of one receipt--with Susan holding down the corners to keep it flat--just to have as an example. The one I photographed was a receipt signed by one of Gideon's sons!

|

Finally

I came to the will itself. I checked the exact date and learned that

James had made out his will a few weeks before his death. The

language took me back to the world of 1817: Knowing that it is

apointed for all Men once to die I so make and publish this my Last

will and Testament.

The

first beneficiary, of course, was his wife Sarah Brown Hays, my third

great-grandmother. The provisions he made for his helpmeet of

fifty-eight years I found quite touching.To

Sarah, James bequeathed the following: two bonds of fifty pounds

each, one bed and beding, one cow (her choice of the flock,) six

sheep, a set of drawers, one-third of the kitchen furniture,

one-fourth of the chairs, and the fire irons. (Evidently all of

the fire irons as no others were designated for other heirs.) Sarah

was also guaranteed the use of the room where I now ly. I

pictured the scribe sitting next to the bed of the dying James Hays,

writing down all his wishes. Was it an attorney? Would it have to

have been an attorney or could anybody have recorded what James

dictated as long as Gideon and the neighbor, William Feron, were

there to witness it? (There's so much I don't know about wills!)

James

further orders that their son, my second great-grandfather Samuel,

find her a horse to ride when she chuses. Later on in the will

he specifies that she and their one unmarried daughter will stay in

the house as long as it suits them and that Samuel, again, will see

that they live in as comfortable acomodations as they have

heretofore had.

Poor

Samuel, the youngest of the family, in charge of everything. Only

twenty-five years old at the time of his father's death, he is

suddenly responsible for sorting out everything—the running of the

farm and seeing that the needs of his mother and his maiden sister

are met. Why doesn't his brother John have to do any of the heavy

lifting? After all, he is the older son and doesn't live that far

away. But maybe Samuel is the responsible one, the one who had stayed

on the scene to farm alongside his father, the one who knows what's

what. I'm sure James had his reasons.

One

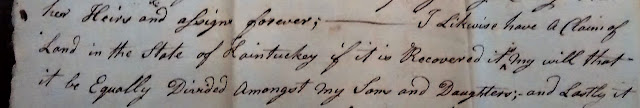

final gem I found in the will was the following: I likewise have a Claim of Land in the State of Kaintuckey if it is Recovered it is my will that it be Equally Divided amongst my Sons and Daughters

I had read in other sources that Lieutenant James Hays had received three tracts of land as payment for his military service in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. One was the Beech Creek property, the second was also in Pennsylvania. But I had never been able to determine the location of the third claim and had always been curious about why he had never followed up on it. Now I'm wondering if, in that packet in the Bellefonte basement, there might be an overlooked scrap of paper holding that information. Perhaps the executors of James's will had attempted to track down the Kaintuckey claim and had reported their success or failure in finding it. (As I say, I know very little about how these things work. Maybe a Wills 101 course should be next in my genealogy self-education.)

James Hays died on February 14, his wife's birthday, in 1817. He was seventy-six years old.

Wednesday, February 21, 2018

52 Ancestors—Week 8 Prompt: Heirloom

The Chair

In the living room of our Denver home, a certain high-backed chair held pride of place between the fireplace and the stairway to the upper level. The woodwork of it scrolled and highly polished, the seat and backrest needle-pointed in Victorian fashion, it was a sight to behold. The backrest of the chair featured a portrait of a high-class lady with piled up hair.

To be truthful, this chair was a bit of a monstrosity. No...that's too strong—an oddity, let's say. In my memory it was enormous, not all that comfortable, and somewhat out of place in the otherwise up-to-date furnishings of our living room. But we loved it—this white elephant/heirloom of ours.

The chair had come to us from Aunt Peg after she died. In fact, it was Aunt Peg's death which had made it possible for Mom and Dad to purchase this new house where the high-back chair was ceremoniously installed. The chair probably wouldn't have been Aunt Peg's choice either, but it was a family heirloom having been needle-pointed by Aunt Frank. (We all referred to her as Aunt Frank, but really she was the aunt of Daddy and Aunt Peg.)

So, Aunt Peg died and there was Aunt Frank's chair and somebody had to have it. You can't just get rid of a chair that was needle-pointed by your ancestor. And so it resided at our family home until 1982, when Mom and Dad decided to leave Denver for the warmer environment of Chapel Hill—without the chair.

Sally had a three-story house, so her top floor was the obvious new home for it. The chair lived there a good twenty years until Sally moved into a Manhattan apartment, and some things had to go. You guessed it: the chair was one of them. Susan was already trying to downsize, and I was in a house so small that most of the living room was already taken up by my piano. The chair was sacrificed. Later, when I became a hoarder of all things family-related, I was shocked that I could have allowed such a thing to happen. How could I have let practicality trump tradition? I mourned the chair.

Sally had a three-story house, so her top floor was the obvious new home for it. The chair lived there a good twenty years until Sally moved into a Manhattan apartment, and some things had to go. You guessed it: the chair was one of them. Susan was already trying to downsize, and I was in a house so small that most of the living room was already taken up by my piano. The chair was sacrificed. Later, when I became a hoarder of all things family-related, I was shocked that I could have allowed such a thing to happen. How could I have let practicality trump tradition? I mourned the chair.

But wait! It turns out that for fifteen years or so, the chair has been sitting, covered by a bedsheet, in Susan’s spare bedroom! It was when I was helping her clear out her house to put it on the market that we uncovered the heirloom. I rejoiced. How could I possibly have thought that we had given up our needle-pointed heirloom? As it must have happened, on that fateful day fifteen years ago, when we were about to consign the chair to the Salvation Army pile, Susan relented at the last moment. She took custody of the chair and has been housing it ever since. I had simply forgotten.

In my memory the chair was of hulking dimensions. In reality, it was small enough to be stowed in my Subaru Impreza hatchback to be hauled home to Vermont. Now, in my newer, somewhat larger house, it sits in the back room— crowded in with the piano. I am waiting for the day that I can pass it off to Abe and his sweetie when they become homeowners and can provide a good setting for the needle-pointed wonder. Maybe they will leave messages for each other on its velvety back.

Thursday, February 15, 2018

Valentine

When you first looked at this picture, did you think, "Huh? WAS? Was what?" Well, that was my thought too. Then I looked at the back of the photo and learned that W.A.S. was a social club at the Western Illinois Normal School where my grandmother Ellen and Arthur, her husband-to-be, were students.

Also on the back of the photograph was the inscription "February 14, 1906." Evidently the club was celebrating Valentine's Day—which also happened to be my grandmother's nineteenth birthday!

Ellen is on the far left in the middle row. It is just possible that the young man in front of her is Arthur. He has the same jug-ears that I've seen in other pictures of my grandfather. But this kid hardly looks like he is twenty-seven, which is the age he would have been when Ellen was nineteen. I wish I knew how to use a facial recognition tool and where to get one.

I have so many questions about this little tableau: Is that Arthur? What does W.A.S. stand for? And what's up with the pictures pinned to some of the men's jackets? Pictures of themselves as babies perhaps? So many questions and nobody to ask.

Monday, February 12, 2018

Favorite Name

Keziah Bellomy was the older sister of my great-grandmother Lucinda Bellomy Odenweller. I always suspected that Keziah was a biblical name, and Wikipedia told me I had been right. Biblical Keziah, one of Job's three daughters, came to symbolize "female equality" because she received an inheritance from her father—not the usual order of things at the time.

I don't know that my Keziah inherited much financially when her father, an Illinois farmer, died in 1876. But, from the little I know of her life as a single woman of strong character and independence, I can't help but think that she lived up to her name.

Keziah was twenty-six and my great-grandmother twenty-one when they became surrogate mothers to their baby nephew Franklin. His mother had died and his father, their brother James, did not feel inclined to care for his four children on his own. I don't know where the baby's older siblings ended up, but Frank was lucky to land with his aunts.

Keziah and Lucinda, both teachers, lived in their father Thomas's household. Their own mother had recently died, so caring for this motherless child must have been both a challenge and a balm. When little Frank was nine years old, Lucinda married and took him with her. He continued to live with my great-grandparents until he married at the age of twenty-three.

Thomas died shortly before Lucinda's marriage in 1876, so I suppose the sisters sold the farm. Keziah moved in with her brother Josiah and his family, according to the 1880 US Census.

Then Keziah left her Illinois home and struck out on her own. She went out west, and lived an independent life—mostly as a school teacher and, later on, as a nurse. According to a US Land Office Record, on December 31, 1890 she bought a 160-acre parcel in Greeley, Kansas. So she must have been a farmer as well!

Her obituary tells that she returned to Illinois for the last four years of her life, spending time with family members. This meant nephews and nieces (and possibly some cousins) because, at seventy-two, she had outlived all but one sibling—the brother who had left home to settle in New Mexico.

When Keziah reached the end of her adventurous (but perhaps lonely) life at the age of seventy-two, she was staying with her nephew Harry. It was in the home of Harry's father Josiah that Keziah had lived in the 1880s before her move to Kansas. Perhaps she and Harry had formed a special relationship during that period. I like to think of her passing her final days in the presence of a loving nephew.

Saturday, January 27, 2018

Another Favorite Photograph

This

is the house in Moline, Illinois where my mother's Swedish

grandparents lived with their six children. My great-grandmother

Stina Ellstrom Ahl proudly poses with her brood in front of the

house. If you zoom in on the photo you can see a ghostly figure in

the window peering out on the proceedings. That would be Stina's

husband, John Albert Ahl. Judging from the few things my mother ever

said about her grandfather, that would seem to be in character. From

my mother's perspective, he was kind of a loner, sat in his chair a

lot reading his Swedish newspaper. It would be like him to literally

take himself out of the picture.

My

grandmother Ellen is the frowny little girl on the left. Next to her

is her younger sister Lillie. The other girl on the bench is Aunt

Phoebe, the oldest of the Ahl children. And the little one in the

long white dress standing in front of the bench? That's my mother's

Uncle Herbert! On the porch in a high chair is baby Aunt Mabelle.

Uncle Leonard has not yet been born, placing this photo in about

1895.

I'm

guessing that this house may have become the Ahl family's home

shortly before the picture was taken. The newly planted sapling to

the left, the somewhat make-shift wooden walkway from the street to

the front door, and what might be the beginning stages of a fence—all

the kind of projects that new homeowners might undertake.

In

2015 I took a trip to Moline to do some family research, and I

located the house at 1029 17th Avenue. It was still recognizable in

spite of having been turned into a duplex. The center window on the

second floor had evidently been sacrificed in the remodeling. Gone

also was the detailed trim of the porch and the roof, replaced with

skimpier, more utilitarian material. And I'm pretty sure that that is

aluminum siding in place of the wooden clapboards on the original

house. The sapling either never

matured at all and died, or it grew too big, cast too much shade, and

was felled. The wooden walkway was replaced with a cement sidewalk.

Still,

the basic appearance of the old Ahl home is nearly the same almost

one-and-a-quarter century later.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)